ARIS: Point It At A Frequency And Let It Tell You The Story

ARIS (Amateur Radio Intelligence System) started as a very simple question: if AI is good at chewing through large amounts of unstructured data and surfacing a few useful insights, what happens if you point it at amateur radio audio instead of WLAN logs? I talked in Prague at WLPC in 2025 about using models as a "digital systems engineer" that reads logs and PCAPs all day so humans do not have to. ARIS takes that same idea and bolts it onto ham radio.

The job is straightforward. ARIS connects to one or more public or private SDR receivers, parks on specific frequencies and modes, and listens. It turns whatever comes across that slice of spectrum into text, tags it with callsigns and timing, and then builds summaries so you can come back later and see what actually happened. It behaves more like a frequency logger that understands context than a band recorder that just dumps audio into a folder.

There is a lot of amateur radio space out there. Picking a place to park a receiver is often harder than wiring the receiver itself. You can leave something glued to 7.200 MHz all night, but the output you get is mostly for entertainment. The real fun with ARIS has been pointing it at places where something structured or interesting is supposed to happen and then letting it tell me how it actually unfolded.

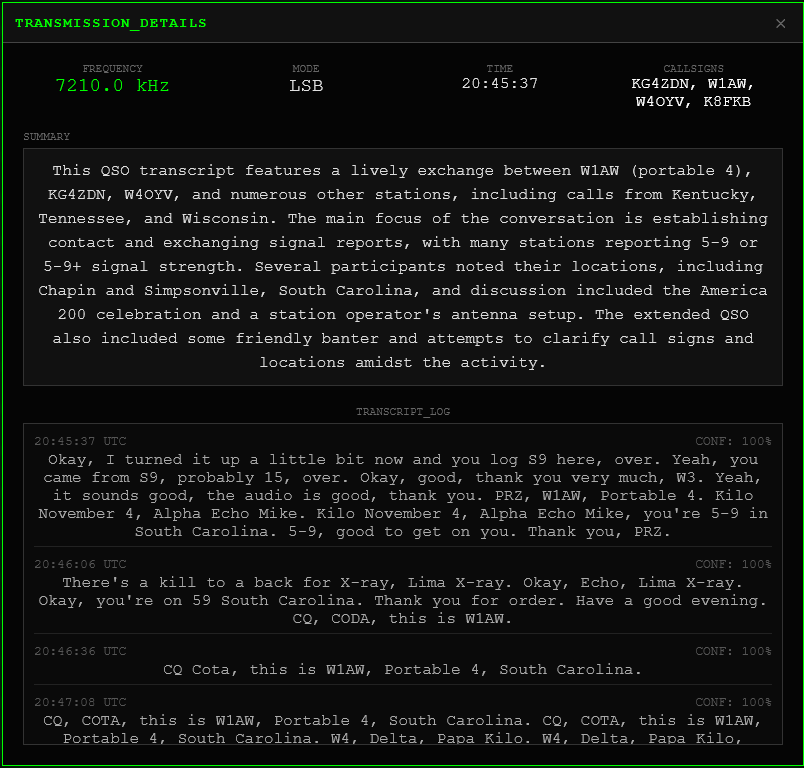

Logging nets and skeds has been the sweet spot so far. If you schedule ARIS to watch 14.300 MHz during the Maritime Mobile Net, you get more than "there was a net." You get a transcript of who showed up, roughly what they were talking about, and a summary of the session that captures the flavor of the "this is our frequency" moments. Finding a cool QSO and pointing ARIS at it has been just as interesting as listening live, because you come away with both the experience and a written record you can search and revisit.

What ARIS Actually Does

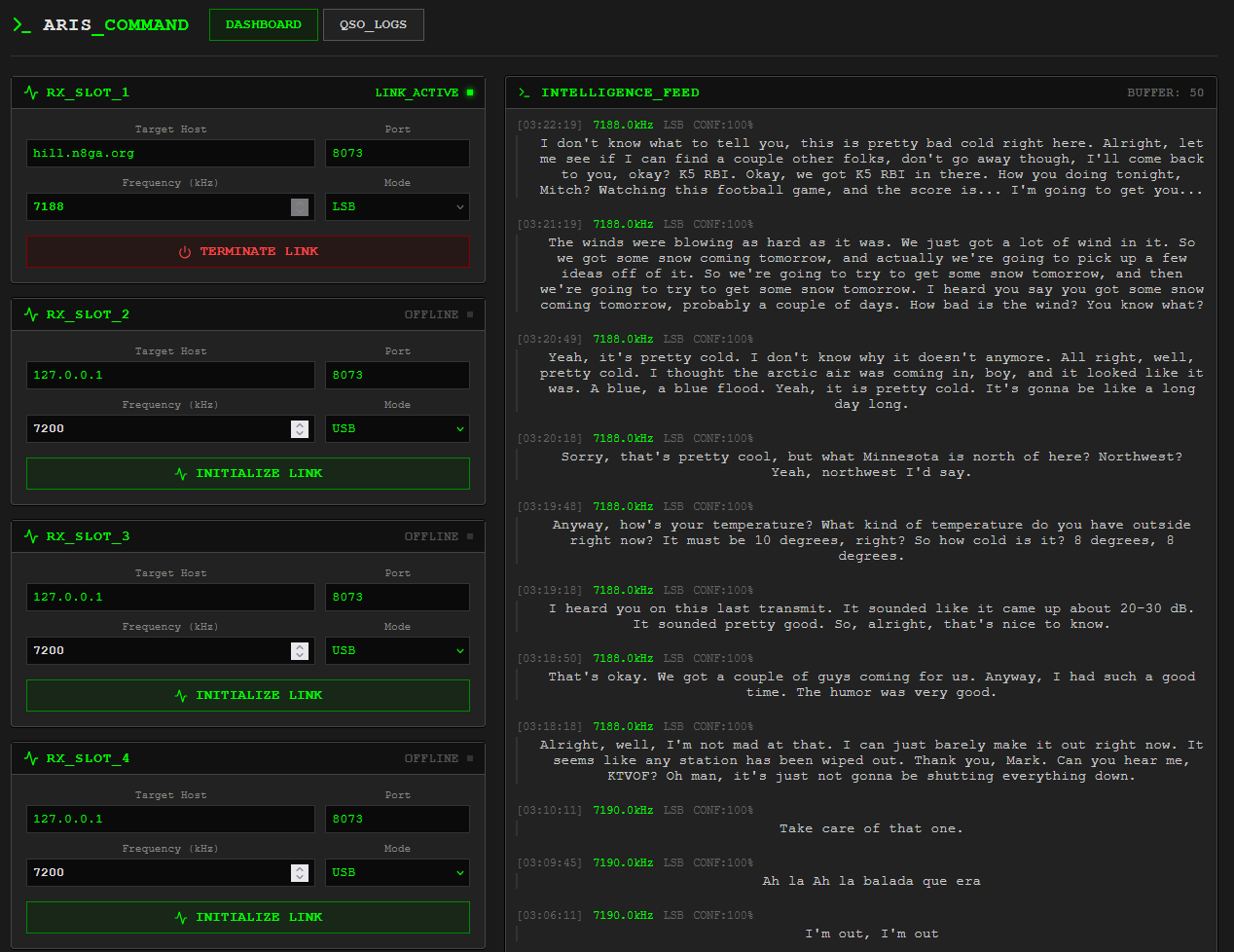

At its core, ARIS tracks one or more "slots." A slot is just a definition of where to listen and how: a KiwiSDR endpoint, a frequency, a mode, and some configuration around how to treat the audio.

For each active slot, ARIS:

- Pulls audio from the SDR and normalizes it enough for downstream processing.

- Runs real‑time speech to text on a local GPU using faster‑whisper.

- Detects the spoken language and, if configured, produces an English translation alongside the original.

- Looks for callsigns and other useful markers in the text stream.

- Groups related activity into sessions that line up with nets, skeds, or longer QSOs.

- Generates a short summary for each session so you can see what that chunk of time was about at a glance.

- For long QSOs or nets, builds a summary‑of‑summaries so you get an overview of the entire event without reading every exchange.

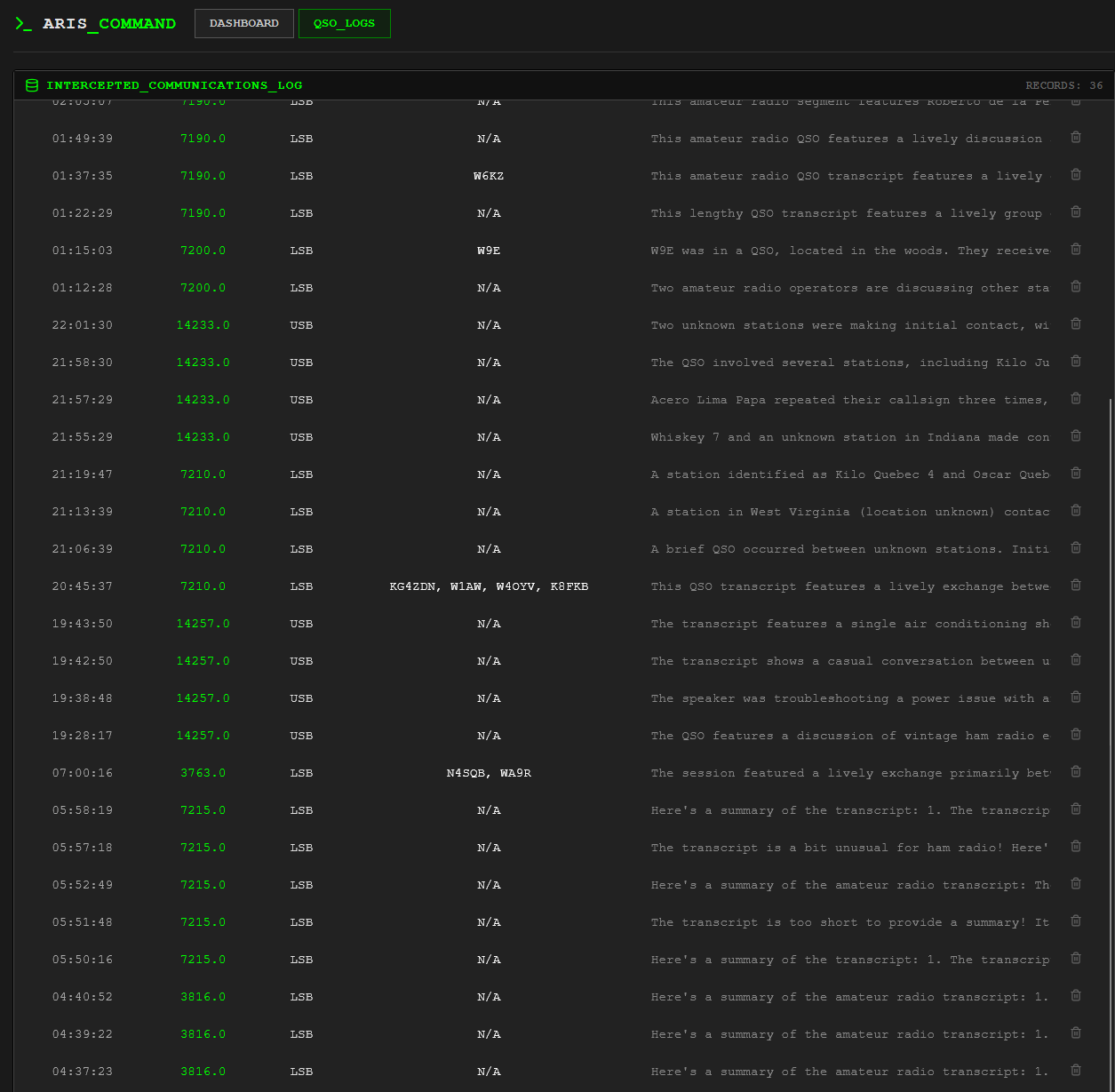

The front end is a web page that shows, per slot, what is happening right now and what has already happened. When you are live, you see text scroll by with only a small delay from the audio. When you come back later, you see a list of sessions for that frequency, each with a transcript, a summary, and, when needed, a condensed "summary of the summaries" at the top.

One of the more surprising parts has been how much more approachable a frequency feels when there is text around it. Coming back to "14.300 from 1900–2000 UTC" as a handful of summaries and transcripts is very different from facing a directory full of WAV files and a good intention to listen "sometime."

How It Is Put Together

Internally, ARIS is a chain of small processes that hand work to each other. That sounds like an architecture diagram, but in practice it has made the system easier to reason about and experiment with.

The capture side only cares about pulling audio off an SDR and keeping it flowing. It knows how to talk to the SDR, handle the passive handshake, keep multiple slots open, and slice the incoming audio into manageable chunks tagged with slot and time. It does not know what a callsign is and does not need to.

Behind that sits the speech engine. It listens to those audio chunks and runs them through a GPU‑accelerated speech‑to‑text model based on Whisper. This is where language detection and translation happen. For each chunk, it emits one or more text segments with timestamps and language tags, and, if you want, a translated English version. This is the point where the shack quietly picks up working comprehension of languages I do not speak.

A small analysis process watches the text stream and tries to recognize callsigns. It applies a mix of pattern matching and phonetic rules to pick out likely calls and attach them to the right points in the transcript. It is not trying to be a full logbook, but it is good enough to answer "who was here" and "when did they appear on this frequency."

On top of that, a sessionizer decides what counts as a single event. Nets and skeds tend to have a natural beginning, middle, and end. ARIS pays attention to gaps in activity and shifts in behavior to group related exchanges into sessions. For each of those, it generates a short summary so you can see quickly what that slice of time was about. When a session runs long, it takes all of those individual summaries and builds a higher‑level summary‑of‑summaries, so you get a compact view of the entire net or QSO before you dive into details.

All of this flows into a small database and an API layer. The database keeps transcripts, summaries, and slot configurations around across restarts. The API lets the web UI ask for "everything that happened on this slot last night" or "the last few sessions where this callsign appeared".

A lightweight message bus sits between the services so they do not have to know much about each other. The capture side publishes audio events, the speech side subscribes to audio and publishes text, the analysis and summarization stages subscribe to text and publish structured events, and the API reads from the database. That separation has been useful whenever a model changes, a new language option appears, or a different way of defining sessions seems worth trying.

Why It Feels Like A Radio Tool

On paper, ARIS touches speech models and language models, but in practice it feels more like another piece of RF test gear than an "AI app".

All the usual radio questions still matter. Which KiwiSDR actually hears this path well? What time of day makes a particular net readable? How does marginal SNR show up in the transcripts and summaries? A receiver in one part of the world will produce a very different text stream from a receiver in another, even when they are tuned to the same frequency.

What changes is the way you interact with a frequency over time. Instead of "I heard something interesting around 14.300 last night," the interface can show "here are the three sessions that ran on 14.300 between 1900 and 2100, here are the callsigns ARIS heard, and here is a paragraph that describes each one". It turns narrow slices of HF into something you can scroll and search like logs, including activity in languages you do not speak.

A good example is a multi‑operator net in Spanish. Live, you hear voices and maybe catch a word here and there. With ARIS pointed at the same frequency, you get Spanish text, an English rendering, and a session summary that tells you who was checking in and roughly what they discussed. It does not replace listening, but it makes it much easier to revisit, share, or reference later.

That is exactly the pattern from the WLPC talk brought into the shack: feed the system a messy stream of unstructured data, let it do the boring parts of normalization and pattern spotting, and then step in as a human when there is something worth caring about.

Frequency‑Level Logging Instead Of Band Scanning

Treating ARIS as a frequency logger rather than a band scanner is important. It is not trying to chase every signal that appears anywhere between two edges. It is trying to sit quietly on specific slices of spectrum and understand them well.

That lines up with how a lot of HF activity is structured in the real world. Nets and skeds anchor themselves to known frequencies at predictable times. If you can point ARIS at those slots, you can build a detailed picture of how they behave: who shows up regularly, how long they run, what kind of traffic dominates, and how that changes over days or weeks.

The same approach works well for one‑off QSOs. It is a familiar experience to stumble across a conversation that sounds interesting but not have the time to sit with it. Being able to assign a slot to that frequency, let ARIS watch it, and then come back later to a transcript and summary has been more satisfying than simply leaving audio playing. There is something about having text you can search, quote, or file away that makes those encounters feel less ephemeral.

Where This Could Go

Two directions seem particularly interesting from here.

The first is watching the same frequency from multiple receivers. HF paths are rarely symmetrical, and the way a conversation sounds from one vantage point can be very different from another. Feeding ARIS audio from several KiwiSDRs tuned to the same frequency and combining their views opens the door to a kind of diversity reception at the text level. If one receiver hears a word cleanly while another loses it in fading, combining their transcripts should give a more complete picture of what was actually said.

The second is lowering the hardware bar. The current build is comfortable on a machine with serious GPUs. That is convenient in a lab, but not a requirement for everyone who might want this kind of capability. A more approachable version would be happy with a single modest server, fewer slots, and smaller models that still handle multiple languages and long sessions without turning everything into mush. The goal is not to squeeze it into the smallest possible box, but to make it reasonable for someone who does not have racks of hardware humming away.

Neither of these changes the basic idea. They just push it further along: better coverage in bad conditions, and more realistic hardware requirements.

Who It Makes Sense For

ARIS sits at a particular intersection: HF listening, remote SDRs, and local compute. It is not meant for everyone, and that is part of the appeal. It makes the most sense if you already enjoy parking on specific frequencies, you are curious about what happens when you are not listening, and you are comfortable running a service or two in the background.

If you have ever thought "I wish I could see what the Maritime Mobile Net looked like last week without replaying everything" or "I keep hearing bits of another language and would like to actually understand it," ARIS starts to feel natural. You point it at the frequencies you care about, let it listen, and then treat the results like a log you can read instead of a signal you might miss.

It is not trying to fix amateur radio or to be a platform. It is a way to let the shack keep an ear on specific places in the spectrum and to turn what it hears into something you can scroll, search, and revisit. The "why" is the same as in that WLPC talk: let machines do the volume work on unstructured data so humans can spend more time on the interesting parts.

Alek (N4OG)